What Placidia thought of the situation we cannot know; there is no reason to believe that she looked with favor upon a life of Christian virginity and retirement; most young girls wish to be married when their contemporaries are. It is not unlikely that she resented the situation, and that she also was irritated by being kept in the background while the less exalted family of Stilicho was preferred to her in the limelight. This visit of the court to Rome beheld a clear example of the power and majesty of Serena, who was less closely connected with the imperial house than Placidia, and whom the latter quite likely secretly detested. In the summer of 404 Melania and Pinianus, a young married couple, sought and obtained an interview with Serena. The two young people, wishing to lead a life of Christian poverty and consecrate themselves to God, desired to sell all they had and give the proceeds to the poor. But both of them belonged to the most wealthy and exalted circles of the Roman aristocracy, and their relatives were much opposed to their literal interpretation of the injunction of Christ. Yet Serena, they thought, would be able by her power and influence to override family opposition, and so it turned out. Serena was able to persuade Honorius o interpose his authority in favor of the two. But the entire account of this transaction is evidence of the power and splendor, who is referred to as empress (basilissa, regina); although the title is technically incorrect, in every way her power and magnificence reflect the majesty of the imperial court. She has her own chamberlain, for example, for whom as well as for Serena the young couple thought it wise to bring rich presents. Serena's intervention of course springs from her Christian piety. It is difficult to avoid the impression that Serena, niece of Theodosius, has put his daughter quite in the background and out of countenance, and that the increasing dislike for her that Placidia was presumably coming to feel was probably in part caused by sheer jealousy.

Stewart Irvin Oost, Galla Placidia Augusta: A Biographical Essay (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 73-4.

| |

Thus began the third Visigothic siege, actually blockade, of Rome, an event whose outcome, after some eight centuries in which the imperial City had known impunity from foreign foes, created a shock of horror from Bethlehem to Britain. Once again Gothic bravery found itself daunted by the walls of Emperor Aurelian; the treachery that the Romans had feared in the beginning of 408 now in fact admitted the Goths by the Salarian Gate, 24 August 410, but not before the City had once again felt the bite of famine. Some buildings were burned, notably the Palace of Sallust the historian, which stood in its magnificence gardens near the gate of entry, perhaps the Basilica Aemilia in the Roman Forum, and the Palace of Saint Melania and Pinianus on the Caelian Hill, then one of the most fashionable quarters of Rome. Palaces and temples were plundered, some persons were slain or tortured to reveal their presumed hidden wealth; some virgins and other females were raped, but churches, especially the basilicas of Saints Peter and Paul, were spared and made places of refuge.

Stewart Irvin Oost, Galla Placidia Augusta: A Biographical Essay (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 96-7.

| |

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Ichnographia Campus Martius (1762), detail.

The Horti Valeriani is situated in the upper right corner, directly above the Horti Sallustiani, which occupies the entire bottom portion of the plan. Note that the Aurelian Wall is delineated via a bowing dotted line, which is visible directly above the words 'Horti' and 'Sallustiani'. The position of the Salarian Gate is indicated along the dotted line, here circled in red.

| |

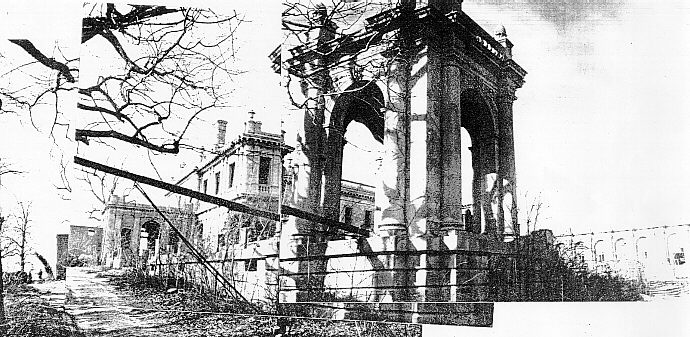

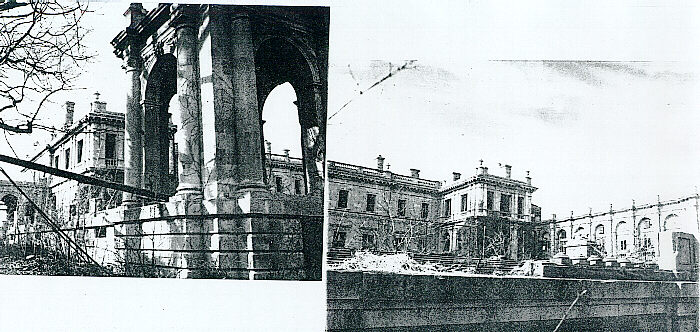

The stock market, in which Mr. Stotesbury operated actively, made a very satisfactory come-back in 1936; but New Deal taxes, including heavier inheritance taxes, were beginning to trouble men of large means. In 1935 Mr. Morgan had sold his father's collection of miniatures, as well as six of his most valuable paintings. We had, however, no inkling of what was to come when in December 1936 Mrs. Stotesbury, who had been a very inactive member of our Committee on Museum, invited her fellow-members out to Whitemarsh Hall for luncheon. The occasion was managed most skillfully. Miss Coleman, Mrs. Stotesbury's secretary, ostensibly included to even the number of men and women, was saying beforehand in the drawing room, "Isn't it too bad about the collection and these dreadful taxes." Thus, sitting by Mrs. Stotesbury, I was prepared for her remarking, at the dessert, that Ned had had to make a change in his will, to direct that the pictures should be sold.

Events of 1937 made this necessary indeed. The market began in February a nose-dive so precipitous as to make the descent of 1929-1933 seem gradual. The New Year's party at the end of 1937 was the last. On May 16, 1938, came Mr. Stotesbury's death.

His will singled out the English portraits, the tapestries, two sets of furniture, the great Isfahan rug and the porcelains from Duveen to be sold. All the rest was left to his wife, including the sculpture. The estate was now reputed to have shrunk again to $5,000,000, but by May 6, 1939, when an accounting was filed, it had recovered to $10,000,000.

Mrs. Stotesbury said at first to Stogdell Stokes, our president, that she feared the sculpture must be her bread and butter. The Palm Beach house was put on the market, with no takers. Duveen must have told the executors he was dying and could not handle the works of art. Knoedler's was said to have been asked to value and dispose of them. Their report could not have been very encouraging. At the darkest moment, on October 7, 1938, Stogdell Stokes and I came out by request of Mrs. Stotesbury to see her before she moved to Washington. The leaves were falling at Whitemarsh Hall. She said the place must be sold, and that she was informed the property would bring more if the house were demolished. She said, "I thought I must sell the sculpture, but, at the figures I am offered, I would much rather give it to the Museum in memory of Ned."

Henri Marceau and I went out again to make selection. We began with the four stone statues by Pajou, the marble by Tassaert, which had belonged to Frederick the Great, and the two Clodion groups of which I had long admired the two matching pieces in the Louvre. The Clodions had come from the lovely salon of the Hótel de Botterel-Quinton in Paris-a building since degraded to receive packing cases as Wanamaker's Paris headquarters. Around them in each of the rotundas were sets of four plaster female figures bearing flambeaux. These, too, we had no hesitation in taking, though they were without any stated provenance or attribution. It was only some years later, when I was looking at Moreau le jeune's wonderful drawing in the Louvre of the inaugural fete of Madame du Barry at Louveciennes in 1771 that I realized that one set, apparently, had stood there on that occasion, in advance of being executed in marble, and that the artists were therefore Pajou, Lecomte and Moyneau.

Mrs. Stotesbury came once, in May 1939, to view the sculpture in place in the west foyer of the Museum, which, as the principal body of French sculpture in America, it so nobly and effectively adorns. She said it would be her last visit to Philadelphia, which she never wanted to see again.

Whitemarsh Hall was advertised for sale in Fortune, as having one hundred and fifty rooms, forty-five baths, four-teen elevators. There were no takers.

In the panic after Pearl Harbor, German planes were reported nearing the coast; the Boston Museum rushed its treasures out of sight. The National Gallery in Washington very intelligently secured the vast empty Vanderbilt chateau of Biltmore in the North Carolina mountains, to shelter the chief masterpieces of the Mellon Collection. The Metropolitan first thought, on the example of the National Gallery in London, of an abandoned mine or quarry, and was on the point of taking one up the Hudson. Fortunately, the prolonged drought during which they inspected it came to an end, and water began to seep in just before they were to occupy it. Various empty country houses were offered them. Soon they announced they had taken a country place, "a hundred miles inland." It was Whitemarsh Hall. Priorities on materials were somehow secured; steel racks for paintings were put up in the salon, steel shutters at the windows. Packing cases were piled in the billiard and other rooms.

Other institutions sent their treasures there also, so that if a single bomb had landed it would have destroyed them all. The hysterical rush to put things in Whitemarsh Hall inspired Hardinge Scholle of the Museum of the City of New York, who had at first participated in the movement, to call the house a "monument hystérique."

The result of the Metropolitan's taking Whitemarsh Hall was indirectly to enrich the Philadelphia Museum. The Stotesbury tapestries, the fine furniture and the great Isfahan, which had remained at the house, were sent at once to the Museum as loans. The paintings, of which but three had meanwhile been sold, followed from New York in June of 1943 to adorn the great drawing room from Lansdowne House which the Museum had just installed and was soon to open.

In October of that year came a new turn. The house was sold to the Pennsylvania Salt Company to house its research laboratories. The reported price, with twenty acres of ground was $167,000--or less than the Metropolitan had spent there on alterations.

Possession was to be taken at the end of the current year of the Metropolitan's lease, the next April first. David Finley of the National Gallery was at luncheon at the Philadelphia Museum the day the sale was announced. He said Francis Taylor had just asked him if they were bringing any of their works back. The answer was no; it wasn't costing them anything at Biltmore (no rent or storage was charged, as the place was making money for the owners as a farm), and they had no room at the National Gallery. If they brought the Mellon pictures back they would have to take down those from the Louvre, which they did not want to do.

Mayor LaGuardia was afraid that the return of the Metropolitan's paintings to New York would cause a relaxation of Civilian defense measures. Poor Francis! After spending all that money it looked as if he would have to find another expensive repository for his pictures. Fortunately his face was saved by the success of the allied arms, and in the spring of 1944 the Metropolitan's pictures returned to New York.

But few strophes remained in the Stotesbury saga. In October of 1944 came an auction in Philadelphia of Mrs. Stotesbury's collection removed from her former residences at Whitemarsh Hall and Marly, the fine house she had meanwhile occupied in Washington, which she then abandoned. Nothing was there on which we cared to bid. In November the remaining objects which Mr. Stotesbury's will had directed should be sold were removed from the Museum for an auction in New York. It was a butchery. One Romney, the Vernon Children brought $22,000, but no other painting fetched more than $10,000. The magnificent fifty-three foot Isfahan carpet brought only $5,000. It had cost Stotesbury $90,000. The whole proceeds of the sale were but $192,075. Duveen must have turned in his grave, or on the spit.

Fiske Kimball, "Grandeur and Miseries of Whitemarsh Hall" in George and Mary Roberts, Triumph on Fairmount: Fiske Kimball and the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1959).

|