2002.12.02 10:20

Re: game talk

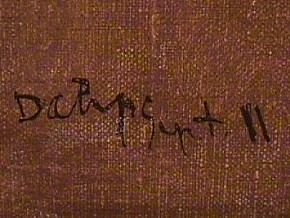

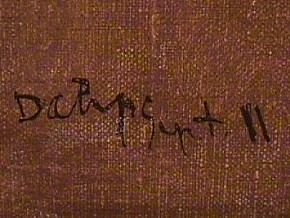

Is it too much to ask that "DuChamp" never appear here again, and that the artist Marcel Duchamp's name is represented here correctly from now on?

Check out Duchamp's own signature...

| |

Do you know Ètant Donnès' back door and that it takes "2 key" to open it? Ètant Donnès' back door plays an integral role within "Projects For Quaestio Abstrusa Fashions"--a work in progress at epicentral/p4qaf. Stephen Lauf

www.quondam.com

www.museumpeace.com ps Might not the window installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art by request of Duchamp for the gallery of The Large Glass be considered a heretofore unacknowledged Duchamp work? Thanks Thomas. I am not familiar with Duchamp Und Die Anderen. Does Daniels write at all about the classical sculptural group within the (exterior) museum pediment above and on axis with the window to the Duchamp gallery at the PMA? This sculptural group, a rare reenactment of classical antique polychromy, represents sacred and profane love via mythological characters. I've been wondering whether Duchamp knew of the symbolism of this group while he was arranging the interior disposition of the Arensberg collection, and specifically the room for the Duchamp collection, and hence the specially installed window. In any case, I like to think of The Large Glass as a confirming furtherance of the sacred/profane love axis at the PMA. (I wonder where Yara is these days.) Steve ps I know the back door to Ètant Donnès cannot be considered a 'work' of Duchamp. Nonetheless, it is the door to what is probably the most (purposefully designed) inaccessible artistic space of the 20th century. pss In a separate email Thomas asked if I scratched "2 KEY" into ET's back door. I did not scratch "2 KEY" into the door. I am not that clever! Moreover, it was Anna's idea to "look into" the back door. Lately, whenever I take a visitor to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, I first take them to the back door, and then tell them they have to find the front door. Looking through the 'arts & literature' sections of Tout Fait, it is clear that many Duchamp inspired artworks are indeed reenactments of one kind or another. It all fits though since even Duchamp reenacted his work--the readymade redux, Boite edition, Green Box, etc. I love reenactment. I write a lot about reenactment. I even owned www.reenactionary.com, but now even that is waiting for a reenactment.

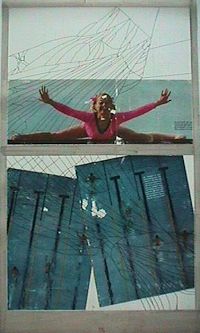

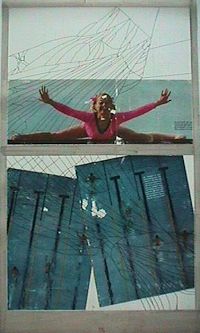

illustrate some 31"x19.5" reenactments of The Large Glass I did in 1993. There were originally (I think) 12 in all. These three are all I have left. The rest are in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston private collections. If there really is an audience for this kind of Duchamp stuff, I might just make all of Museumpeace a Duchamp reenactment (of one kind or another), at least for some period of time. Is G. Farriz showing us that it is now a paradox to try and try again even if one does first succeed? Go in Museumpeace, and may Museumpeace be with you. So I was correct? You are indeed trying and trying again even though you already first succeeded? My mother speaks with a genuine German accented English, and so do I (when I want to amuse) for that matter. Gosh, I hope that stuff you write isn't supposed to be a French accented English, because that is completely lost in my translation. I just got done watching this great TV show called Rollover-Play. It's mostly a display of un-air-conditioned thespians followed by a reward ceremony lauding the best over-actor. I could barely hold back the tears. The above is an excerpt from: Stephen Lauf, Learning From Lacunae: A Progressive Inquiry of the Acquisition of Knowledge Via Reflection On What Is Not There (Philadelphia: Museumpeace, 2003), p. 19120. ad carceres a calce revocari I looked at Yvonne and Magdeleine Torn in Tatters at the Philadelphia Museum of Art this afternoon, and took some digital snapshots of the painting as well. Later, at home, looking at a close-up image of the painting's signature, I notice it is signed "Duchamp Sept 11". I find out the date means September 1911, but I still think the coincidence is interesting. Perhaps I'll start referring to the quondam World Trade Center towers as Yvonne and Magdeleine. There is a special Richard Hamilton Museum Study exhibit within the PMA Duchamp gallery--see www.philamuseum.org for details. I might upload some images of the exhibit at Museumpeace next month. Someone has left additional graffiti on Étant Donnés' back door--"BOAC Scoota Allegheny 2002". This graffiti was not there about a month ago. I have over 40 digital images of The Large Glass (in full and in detail) in situ at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The images were taken at various times since February 1999. Since all the contemporary art galleries of the PMA were renovated winter/spring 2000, I also have Large Glass in two different immediate "contexts". There is even one fortuitous shot of two real "bachelors" standing behind and seen through the glass. These images were taken for my own [artistic] use, but I have no problem with sharing some of them as long as I know what they will be further used for and that proper photographic credit for the image(s) is thereafter provided. Stephen Lauf www.quondam.com www.museumpeace.com Museum Trip 2001.03.25 entitles a display beginning at wmpc/01/0050.htm comprising a series of images recorded at the Philadelphia Museum of Art on 25 March 2001. These images, rendered here at approximately the size of slide images on a light table, are ordered in the exact sequence that they were taken. More than half of the images depict an investigation of what other works of art at the Philadelphia Museum are axial with The Large Glass. For example, immediately adjacent the Duchamp gallery are galleries containing the works of Brancusi and Twombly respectively. Directly above the Duchamp gallery is a room by 18th century Scottish architect Robert Adam. In the museum's other wing across the courtyard is a fine collection of American glass, (a fitting symmetrical counterpoint to The Large Glass), a collection of Pennsylvania German artifacts, and on the floor above a selection of temples from the Orient. Inspiration for this investigation derives from the very strong axial relationship between Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even and Jennewein's Western Civilization as clearly manifest on the Philadelphia Museum of Art's northern courtyard facade, as well as the quondam axial relationship between The Large Glass and Martin's Yara. Museum Trip 2001.03.25 further considers the other axial, albeit by chance, occurrences at Philadelphia with regard to The Large Glass, and, as chance would have it, it was during the recording of the Brancusi gallery that the chance 'discovery' of Étant Donnés inscripted back door occurred. The following was first sent today to the Design-L listserve: [The following is the first two paragraphs, etc. of "What the Hand Knows" by Calvin Tomkins. This articled first appeared in The New Yorker 2 May 1983. This article very much spurred my attitude toward CAD (computer aided design) and its relationship to draftsmanship and manual dexterity in general. It also very much stimulated the initiation of my 'career' as an artist. For the record, I received CAD training February 1983, and CAD equipment was delivered to Cooper and Pratt Architects (my employers then) April 1983.] "What the Hand Knows" One of our era's significant feats has been the separation of art from skill. In most English dictionaries, the two words are closely linked. "Art" spreads a wider net, of course; it is so variable in meaning that, according to Webster, it can be used as a synonym for "skill," "cunning," "artifice," and "craft"--"which, on the other hand, are not always synonymous among themselves." When it comes to the creation of works of art, most people would agree that something more than skill, cunning, artifice, and craft is required. Only in this century, however, has it been found possible and desirable to produce works of art whose making requires little skill or none whatsoever. Marcel Duchamp is generally thought to be the hero (or the villain, if you prefer) of this remarkable achievement. Duchamp's famous "ready-mades"--common manufactured objects, such as an iron bottle-drying rack and a snow shovel, selected and signed by the artist--undermined the whole tradition of the artist as a skillful maker while poking fun at the belief that artists were superior beings whose mere signature conferred value. Duchamp's ambition, as he explained it, was "to put painting once again at the service of the mind." European painting since Courbet had been primarily "retinal," he said--a matter of manual skill in applying paint to canvas. By choosing a factory made object of no aesthetic interest, which he might alter slightly or else leave untouched, Duchamp was calling attention, in his ironic way, to the fact that a work of art was also an intellectual act--a choice, a sum of decisions. (Years later, when an art historian taxed him with the fact that several of his ready-mades had in the course of time become highly prized works of sculpture--icons reproduced in all the art-history books--Duchamp smiled and said, "Nobody's perfect, hm?" [Five paragraphs later:] Anyone who goes around to the galleries these days, however, is bound to see a great deal of deliberately unskillful, clumsy-looking work. Jean Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and the other "graffiti artists" who have shifted their efforts from subways to shows in New York galleries and international "trend" exhibitions are much talked about this season, and the European and American neo-expressionists are still the hot ticket in SoHo. This slapdash, loosely figurative painting is usually viewed as a triumphant reaction to the austerities of Minimalism and Conceptualism. Perhaps it is; perhaps that is all it is. David Hockney, the English artist, has been saying recently that representational art was bound to make a comeback sooner or later; the reason its return took the form it has taken in neo-expressionist, "new image," and graffiti art, he said, is that these artists were never trained to draw. Some of our young geniuses gain an appearance of free hand drawing by projecting photographic images on their canvases and tracing them; the photograph is, among other things, an invaluable substitute for skill. [note: almost 20 years later Hockney makes well researched claims that even some older masters used projections to draw!] [When the CAD computer equipment finally arrived and was up and running at Cooper and Pratt Architects, we had one of those not-too-serious office competitions for naming the computer. I suggest we call it 'Duchamp' while Bernie (my CAD partner then) suggested 'Godot' (as in "Waiting for Godot"). As it happened, both Bernie's and my suggestion turned out to be fitting. What I personally experienced when CAD became my daily occupation was the sudden obsolescence of my (quite talented) drafting skills. I still used my hands to "draw," but my dexterity now amounted to making sure I pushed the right buttons--my mother very presciently at the time made the analogy to playing the piano. I started seeing the final drawings produced by either pen-plotter or electrostatic printer as sort of "ready-mades" or at least abundantly reproducible "originals" that I could merely add a signature to in order to confer them as "my" drawings. Luckily (and thanks to the words of Calvin Tomkins, I guess), I found an outlet for my quondam drafting skills in producing "art." I decided, however, that I no longer needed to exhibit skill because I had (access to) a machine that did that, thus I produced art that was (and sometimes still is) deliberately unskillful, intending to prove through such imperfect manifestations themselves that a hand indeed created the work. If nothing else, all of the above explains why a few years ago here at design-l I wrote that "perhaps it is more the case that the way we think influences the way we use tools."] Museum Trip 2002.09.15 is the latest edition of the MUSEUM TRIP series at

1072m.

1072m

contains images of Richard Hamilton's reenactment of Oculist Witnesses (within a gallery containing other recently/temporarily installed Hamilton works, and a number of mostly detail images of Yvonne And Magdeleine Torn In Tatters.

1072m

contains images of Hamilton's Museum Studies 6, essentially another reenactment (albeit in paper) of The Large Glass with lots of notes added. [For the record, I first became familiar with the work of Thomas Struth, particularly his museum photographs, when his work appeared on the cover of Artforum May 2002. I've been taking pictures at the Philadelphia Museum of Art since February 1999 (see Steve Visits the Local Acropolis beginning at wqc/04/0326.htm), that is, shortly after I purchased a digital camera that I happily found took good interior pictures without a flash. As it happens, one of Struth's museum pictures is presently on display at the PMA, thus the continued image and reality mirror play within

1072m.]

Patricia, I will be happy to add my (own) signature to your painting. This (apposite?) apposition on my part may well increase the value of your (faux?) Duchamp in time. Don't worry, I can be very cheap. Steve Primarily Not Duchamp, an exhibit at Venue (a quondam art gallery in Philadelphia) November 1993, is presently reenacted at wireframe/VENUE at

1072p.

Follow the links at the bottom of each page's entry and you will then eventually have seen all the works currently available for viewing. The title of the exhibit derives from the cracks of The Large Glass being "primarily not Duchamp." There are other clues within certain works as to how the exhibits fits together, and these will be explained when each work is more fully explained (maybe within the next couple of weeks).

Cher (and cher alike) Bill: First off, I think you're lying when you say, "I can't find your Duchampiana," but then again, maybe you're telling the truth since the exhibit is indeed called "Primarily Not Duchamp" suggesting (at least) that the exhibit was/is primarily something other than Duchamp(iana). You say you fell into a statement (of) mine, while I and my work fell into (or is it through?) the cracks it seems, at least from my perspective relative to yours. [Then again, maybe you just didn't 'get' the hyperlinks (and thus didn't view the exhibit at all), which is understandable, but not necessarily tolerable.] Ah, the (ongoing sterotypic) clichés regarding art and wall, artist and architect; one thinks how primitive it all really is, the notion of art on (cave) walls, that is. Plus, who exactly are these "architects [that] hate painting so much that they take up painting to show how to make a work of virtual space that does not push the walls around in actual space? I'm requesting you provide evidence! And, as to "transmorgification into bits in virtual space" isn't that more or less exactly what Duchamp did himself to his own art via De Ou Par Marcel Duchamp Ou Rrose Selavy (1935-41)? You can still see virtually all the walls of my house starting at

illustrate some 31"x19.5" reenactments of The Large Glass I did in 1993. There were originally (I think) 12 in all. These three are all I have left. The rest are in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston private collections. If there really is an audience for this kind of Duchamp stuff, I might just make all of Museumpeace a Duchamp reenactment (of one kind or another), at least for some period of time. Is G. Farriz showing us that it is now a paradox to try and try again even if one does first succeed? Go in Museumpeace, and may Museumpeace be with you. So I was correct? You are indeed trying and trying again even though you already first succeeded? My mother speaks with a genuine German accented English, and so do I (when I want to amuse) for that matter. Gosh, I hope that stuff you write isn't supposed to be a French accented English, because that is completely lost in my translation. I just got done watching this great TV show called Rollover-Play. It's mostly a display of un-air-conditioned thespians followed by a reward ceremony lauding the best over-actor. I could barely hold back the tears. The above is an excerpt from: Stephen Lauf, Learning From Lacunae: A Progressive Inquiry of the Acquisition of Knowledge Via Reflection On What Is Not There (Philadelphia: Museumpeace, 2003), p. 19120. ad carceres a calce revocari I looked at Yvonne and Magdeleine Torn in Tatters at the Philadelphia Museum of Art this afternoon, and took some digital snapshots of the painting as well. Later, at home, looking at a close-up image of the painting's signature, I notice it is signed "Duchamp Sept 11". I find out the date means September 1911, but I still think the coincidence is interesting. Perhaps I'll start referring to the quondam World Trade Center towers as Yvonne and Magdeleine. There is a special Richard Hamilton Museum Study exhibit within the PMA Duchamp gallery--see www.philamuseum.org for details. I might upload some images of the exhibit at Museumpeace next month. Someone has left additional graffiti on Étant Donnés' back door--"BOAC Scoota Allegheny 2002". This graffiti was not there about a month ago. I have over 40 digital images of The Large Glass (in full and in detail) in situ at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The images were taken at various times since February 1999. Since all the contemporary art galleries of the PMA were renovated winter/spring 2000, I also have Large Glass in two different immediate "contexts". There is even one fortuitous shot of two real "bachelors" standing behind and seen through the glass. These images were taken for my own [artistic] use, but I have no problem with sharing some of them as long as I know what they will be further used for and that proper photographic credit for the image(s) is thereafter provided. Stephen Lauf www.quondam.com www.museumpeace.com Museum Trip 2001.03.25 entitles a display beginning at wmpc/01/0050.htm comprising a series of images recorded at the Philadelphia Museum of Art on 25 March 2001. These images, rendered here at approximately the size of slide images on a light table, are ordered in the exact sequence that they were taken. More than half of the images depict an investigation of what other works of art at the Philadelphia Museum are axial with The Large Glass. For example, immediately adjacent the Duchamp gallery are galleries containing the works of Brancusi and Twombly respectively. Directly above the Duchamp gallery is a room by 18th century Scottish architect Robert Adam. In the museum's other wing across the courtyard is a fine collection of American glass, (a fitting symmetrical counterpoint to The Large Glass), a collection of Pennsylvania German artifacts, and on the floor above a selection of temples from the Orient. Inspiration for this investigation derives from the very strong axial relationship between Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even and Jennewein's Western Civilization as clearly manifest on the Philadelphia Museum of Art's northern courtyard facade, as well as the quondam axial relationship between The Large Glass and Martin's Yara. Museum Trip 2001.03.25 further considers the other axial, albeit by chance, occurrences at Philadelphia with regard to The Large Glass, and, as chance would have it, it was during the recording of the Brancusi gallery that the chance 'discovery' of Étant Donnés inscripted back door occurred. The following was first sent today to the Design-L listserve: [The following is the first two paragraphs, etc. of "What the Hand Knows" by Calvin Tomkins. This articled first appeared in The New Yorker 2 May 1983. This article very much spurred my attitude toward CAD (computer aided design) and its relationship to draftsmanship and manual dexterity in general. It also very much stimulated the initiation of my 'career' as an artist. For the record, I received CAD training February 1983, and CAD equipment was delivered to Cooper and Pratt Architects (my employers then) April 1983.] "What the Hand Knows" One of our era's significant feats has been the separation of art from skill. In most English dictionaries, the two words are closely linked. "Art" spreads a wider net, of course; it is so variable in meaning that, according to Webster, it can be used as a synonym for "skill," "cunning," "artifice," and "craft"--"which, on the other hand, are not always synonymous among themselves." When it comes to the creation of works of art, most people would agree that something more than skill, cunning, artifice, and craft is required. Only in this century, however, has it been found possible and desirable to produce works of art whose making requires little skill or none whatsoever. Marcel Duchamp is generally thought to be the hero (or the villain, if you prefer) of this remarkable achievement. Duchamp's famous "ready-mades"--common manufactured objects, such as an iron bottle-drying rack and a snow shovel, selected and signed by the artist--undermined the whole tradition of the artist as a skillful maker while poking fun at the belief that artists were superior beings whose mere signature conferred value. Duchamp's ambition, as he explained it, was "to put painting once again at the service of the mind." European painting since Courbet had been primarily "retinal," he said--a matter of manual skill in applying paint to canvas. By choosing a factory made object of no aesthetic interest, which he might alter slightly or else leave untouched, Duchamp was calling attention, in his ironic way, to the fact that a work of art was also an intellectual act--a choice, a sum of decisions. (Years later, when an art historian taxed him with the fact that several of his ready-mades had in the course of time become highly prized works of sculpture--icons reproduced in all the art-history books--Duchamp smiled and said, "Nobody's perfect, hm?" [Five paragraphs later:] Anyone who goes around to the galleries these days, however, is bound to see a great deal of deliberately unskillful, clumsy-looking work. Jean Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and the other "graffiti artists" who have shifted their efforts from subways to shows in New York galleries and international "trend" exhibitions are much talked about this season, and the European and American neo-expressionists are still the hot ticket in SoHo. This slapdash, loosely figurative painting is usually viewed as a triumphant reaction to the austerities of Minimalism and Conceptualism. Perhaps it is; perhaps that is all it is. David Hockney, the English artist, has been saying recently that representational art was bound to make a comeback sooner or later; the reason its return took the form it has taken in neo-expressionist, "new image," and graffiti art, he said, is that these artists were never trained to draw. Some of our young geniuses gain an appearance of free hand drawing by projecting photographic images on their canvases and tracing them; the photograph is, among other things, an invaluable substitute for skill. [note: almost 20 years later Hockney makes well researched claims that even some older masters used projections to draw!] [When the CAD computer equipment finally arrived and was up and running at Cooper and Pratt Architects, we had one of those not-too-serious office competitions for naming the computer. I suggest we call it 'Duchamp' while Bernie (my CAD partner then) suggested 'Godot' (as in "Waiting for Godot"). As it happened, both Bernie's and my suggestion turned out to be fitting. What I personally experienced when CAD became my daily occupation was the sudden obsolescence of my (quite talented) drafting skills. I still used my hands to "draw," but my dexterity now amounted to making sure I pushed the right buttons--my mother very presciently at the time made the analogy to playing the piano. I started seeing the final drawings produced by either pen-plotter or electrostatic printer as sort of "ready-mades" or at least abundantly reproducible "originals" that I could merely add a signature to in order to confer them as "my" drawings. Luckily (and thanks to the words of Calvin Tomkins, I guess), I found an outlet for my quondam drafting skills in producing "art." I decided, however, that I no longer needed to exhibit skill because I had (access to) a machine that did that, thus I produced art that was (and sometimes still is) deliberately unskillful, intending to prove through such imperfect manifestations themselves that a hand indeed created the work. If nothing else, all of the above explains why a few years ago here at design-l I wrote that "perhaps it is more the case that the way we think influences the way we use tools."] Museum Trip 2002.09.15 is the latest edition of the MUSEUM TRIP series at

1072m.

1072m

contains images of Richard Hamilton's reenactment of Oculist Witnesses (within a gallery containing other recently/temporarily installed Hamilton works, and a number of mostly detail images of Yvonne And Magdeleine Torn In Tatters.

1072m

contains images of Hamilton's Museum Studies 6, essentially another reenactment (albeit in paper) of The Large Glass with lots of notes added. [For the record, I first became familiar with the work of Thomas Struth, particularly his museum photographs, when his work appeared on the cover of Artforum May 2002. I've been taking pictures at the Philadelphia Museum of Art since February 1999 (see Steve Visits the Local Acropolis beginning at wqc/04/0326.htm), that is, shortly after I purchased a digital camera that I happily found took good interior pictures without a flash. As it happens, one of Struth's museum pictures is presently on display at the PMA, thus the continued image and reality mirror play within

1072m.]

Patricia, I will be happy to add my (own) signature to your painting. This (apposite?) apposition on my part may well increase the value of your (faux?) Duchamp in time. Don't worry, I can be very cheap. Steve Primarily Not Duchamp, an exhibit at Venue (a quondam art gallery in Philadelphia) November 1993, is presently reenacted at wireframe/VENUE at

1072p.

Follow the links at the bottom of each page's entry and you will then eventually have seen all the works currently available for viewing. The title of the exhibit derives from the cracks of The Large Glass being "primarily not Duchamp." There are other clues within certain works as to how the exhibits fits together, and these will be explained when each work is more fully explained (maybe within the next couple of weeks).

Cher (and cher alike) Bill: First off, I think you're lying when you say, "I can't find your Duchampiana," but then again, maybe you're telling the truth since the exhibit is indeed called "Primarily Not Duchamp" suggesting (at least) that the exhibit was/is primarily something other than Duchamp(iana). You say you fell into a statement (of) mine, while I and my work fell into (or is it through?) the cracks it seems, at least from my perspective relative to yours. [Then again, maybe you just didn't 'get' the hyperlinks (and thus didn't view the exhibit at all), which is understandable, but not necessarily tolerable.] Ah, the (ongoing sterotypic) clichés regarding art and wall, artist and architect; one thinks how primitive it all really is, the notion of art on (cave) walls, that is. Plus, who exactly are these "architects [that] hate painting so much that they take up painting to show how to make a work of virtual space that does not push the walls around in actual space? I'm requesting you provide evidence! And, as to "transmorgification into bits in virtual space" isn't that more or less exactly what Duchamp did himself to his own art via De Ou Par Marcel Duchamp Ou Rrose Selavy (1935-41)? You can still see virtually all the walls of my house starting at wmpc/05/0457.htm and the 130 odd pages that follow. Mind you, these images reflect the conditions of my house January 2001, thus providing, in some cases, a pre-altered view.

Thanks for extending Primarily Not Duchamp into performance. Peace. Steve ps Feel free to ask this architect's "view on painting." Satisfaction primarily not guaranteed, however. Bill, take a moment, a real true moment, and reflect on how YOU began this conversation. You're saying "I can't find your Duchampiana" has a distinct ring of disingenuousness, and I would be lying if I didn't say that is what I think. I was being honest; I'm not sure you were. I also think YOU are somewhat upset that you did not end my Duchamp conversation(s), which are far, far from being over. S The point could be made that excremental and reproductive functions do not exactly overlap within the human body. Excrement, while generally defined (in Webster's Third New International Dictionary, 1966) as 'waste matter discharged from the body' usually refers to 'waste discharged from the alimentary canal,' hence fecal matter. More correctly then, reproductive functions overlap with the urinary tract. Note that urine is a product of metabolism, while excrement is a product of assimilation (in the extreme, i.e., purge). Besides being reenactments (of mistletoe, even?), are today's Duchamp FOUNTAINs also representations of the "male fig leaf"? Or might they enforce artistic blabber control? (I wish.) Or do they portend that "in the future, everyone will piss for 15 minutes?" Frank Zimmerman wrote in closing: i kan hardly waite for 'ZTiffAN'to hurll hiz VORboze into THiz MIXX-KAN U & by the TIme 'THe RAiny-BUFfollow putzz IT toGETHER WE'll B zunning OURzelvez-a LONGway from PHillee' Steve replies: I could be cute and say I really should delay any 'hurl' coming from my direction, or more specifically from my Philadelphia position, but the truth is that I enjoy this bulletin board and it ongoing postings. I enjoy the stimulation as well as the open opportunity engendered by the bulletin board. Of course, this is because I even more enjoy the stimulation and open opportunity engendered by Duchamp and his works. My first visit to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (in 1972 when I was a sophomore in high school) was spurred on by LIFE magazine's feature of the world's largest painting by Gene Davis

(see 9827).

It was on that first visit that I at least remember seeing The Large Glass for the first time, but with no prior knowledge of it or Duchamp--perhaps in retrospect experiencing a kind of lose of virginity in the process, yet also oddly not knowing then who was ultimately "fucking" with me. I wasn't crazy about what I saw, but the full title of the piece did indeed "tickle" me. Beyond that, I can now only guess that I probably didn't see into Étant Donnés that first visit, thus I probably saw the door, but didn't know to look inside. Sometime it seems like a lot has happened (with me) in the 30 years since then, and sometimes it seems that maybe not enough happened since then. And then even delay becomes an issue, and I suppose that's appropriate (or is it just cute?). One work at the PMA that I clearly remember from my first visit is the very early Picasso Self Portrait in its collection (currently on an exhibition tour). Picasso was still alive then, but he died the next year. I remember how TIME magazine began it report of Picasso's death, something to the effect of moving from "Picasso IS the greatest artist of the 20th century to Picasso WAS the greatest artist of the 20th century." I've just now been inspired to consolidate my Philadelphia Museum of Art focus via (working title) Reenacting Triumph on Fairmount, Even. Having thus been prompted by YaLing Chen's post, I went to read "The Creative Act" within a copy of the latest reprint of Salt Seller, a book I purchased at the Philadelphia Museum of Art something like two years ago. I know I never read this book cover to cover, but I probably read the short 'essays' when I first bought the book. Anyway, before reading "The Creative Act" today, I first (re?)read the text right before it, namely, "Regions which are not ruled by time and space....", text of a television interview of Duchamp by James Johnson Sweeney January 1956 filmed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. [I was in Philadelphia at the time, but still in my mother's womb, waiting for the last hours before Spring it turned out.] This reading turned out to be completely apropos because earlier today I composed and uploaded a series of webpages entitled Dossier Duchamp--4580 and follows--which comprise [almost] all the images I taken of the Duchamp Gallery at the Philadelphia Museum of Art since 11 February 1999. Being now more aware of "Regions which are not ruled by time and space...." I propose Museum Studies 6.1 where visitors to the PMA Duchamp Gallery are encouraged to bring along a copy of the Duchamp/Sweeney interview text and then speak some of the passages while in the Duchamp Gallery, thus somewhat closely reenacting sound waves first produced by Duchamp and/or Sweeney within the same space, yet at a different time, obviously. The next time I visit the PMA Duchamp Gallery you can be sure I'll reenactingly speak "There is a symmetry in the cracking, the two crackings are symmetrically arranged and there is more, almost an intention there, an extra--a curious intention that I am not responsible for, a ready-made intention, in other words, that I love and respect." The notion of casting Duchamp in the nude might be all that is needed to ensure success, with occasional slips into drag, of course. And that line, "Oddly enough, the crack of my ass is a ready-made" gets the audience howling every time. ["Don't tell me. I noticed it too. Something sphinx in here again."] Then is there the competing notion of an enormous Duchamp dream of a chess game with the opponent unknown, yet all the pieces are actual personalities. For example, Duchamp's Queen is Michelangelo and Duchamp's King is Rrose Selavy, while the opponent's Queen is Elizabeth II and the opponent's King is Michelangelo. [One has to wonder if playing with a real Queen has its advantages.] As usual, one of Duchamp's Bishops is Pope St. Celestine V, the one that "was unfitted for the papal office in every respect except his holiness." And, with any luck, the peon's are dedicated people like you and me. "Positioning Etant Donnes" [from Jennifer Gough-Cooper's chronology (Ephemerides) within Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life (1993) with notes/questions by myself]: 6 May 1949. Philadelphia ...and Duchamp makes detailed notes on the architecture of the different rooms [of the Philadelphia Museum of Art where the Arensberg Collection ultimately ends up]. I wonder if these detailed notes still exist somewhere, and whether they might offer an indication that Duchamp in 1949 at least knew of the space in the PMA where Étant Donnés is ultimately housed. 20 March 1961. Philadelphia In the evening, with Katherine Kuh as moderator, Duchamp, the sculptor Louise Nevelson, and two painters, Larry Day and Theodoror Stamos, are members of a panel to discuss "Where do we go from Here?" at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art. Of the panelists, Duchamp is the only one to make a prepared statement. [All of the 20 paragraph statement is published in full within the chronology, and ends with, "The great artist of tomorrow will go underground." Roger LaPelle, in Tout Fait's Notes issue 1, no. 3, writes of Duchamp's visit/lecture at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1962 where Duchamp refers to himself as an "underground artist." [I was in Philadelphia on 20 March 1961, but I was not listening to Duchamp downtown, rather, I was at home (in the same house I'm in right now) celebrating my 5th birthday (no kidding), and I distinctly remember thinking at the time, "where do I go from here? (just kidding)] Has the above mentioned text been published anywhere else beside the Gough-Cooper chronology? It is a very provocative/prescient late Duchamp text. 31 March 1968. New York [the entry ends with] However, the question of the ultimate presentation of Etant donnes preoccupied Marcel. He finally decided that the one person who might help him solve this problem was Bill Copley. When Marcel first told him the story of the piece Bill could not wait to see it, and readily accepted to present the "demountable approximation" in the name of the Cassandra Foundation to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, if the trustees would accept it. What I am interested in is whether Duchamp's involvement in the installation of the Arensberg Collection (roughly 1949 to 1954) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art has any direct bearing on the on-going creation and ultimate position/presentation of Étant Donnés. I'll pursue all this (I hope) at the PMA library, but if there is already a published study of Duchamp's role vis-a-vis the PMA installation of the Arensberg collection I would much appreciate being made aware of it. I went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) Library two Tuesdays ago, but alas that is not the place to conduct research regarding Duchamp's involvement vis-à-vis the Arensberg collection and its ultimate residing within the PMA. The Museum Archives is the place to do the research, but it just so happens that the Museum Archives have just begun the large project of organizing all the Arensberg/Duchamp archived material. [Do some people at the PMA read this bulletin board? I know that at last d'Harnoncourt reads Tout Fait.] Nonetheless, I did find out that the rooms that now contain Étant Donnés and the visitors/viewers quarters were storage rooms before--at least that's what an older librarian(?) at the PMA remembers. At this point, for me at least, it seems reasonable to believe that Duchamp was well aware of the (future Étant Donnés) space at the PMA while he was secretly working on Étant Donnés in NY, and that quite possibly this knowledge made it easier to work "underground" since what he was doing was already going to be a museum piece. If Étant Donnés is Duchamp's great underground work, is his activity at the PMA, especially his organizing of his own works within the museum, Duchamp's great above-ground work of the same period? The original printing of the Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin of 1969 that introduced Étant Donnés contains a forward where "Dr. Evan Turner described the long relationship between Marcel Duchamp and the PMA..." [I have yet to read this text.] Chapter 18 of Triumph on Fairmount: Fiske Kimball and the Philadlphia Museum of Art (1959) is entitled "The Arensbergs" and comprises a series of letters by Kimball that describe each of his visits with the Arensbergs in LA. entertaining anecdote from Triumph on Fairmount, p. 299: The next day, Ingersoll was in the Arensberg galleries when Fiske came in with Perry Rathbone, the new director of the Boston Museum. This is the 'big glass,'" he said, pointing to a large shattered pane of glass decorated with oil paint and lead wire in abstract patterns, which was mounted on a stand in front of the window looking out on the courtyard. "Duchamp called it The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even." He laughed and went on in a loud voice to make several vulgar remarks. "Fiske, you cannot talk like that here. Remember you are in a public place." "I'll talk as I please," said Fiske. "You aren't my boss any more." Rathbone did not know what to make of this passage, for it was not until the following Tuesday, January 25, 1955 that Fiske's resignation was published. [Museum Studies 6.2: on any given January 19 go stand in front of The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even and laugh and make several vulgar remarks.]

Stephen Lauf

The Self Portrait Regarding Duchamp

2002.12.02

digital text: all the Lauf text posted at the Duchamp Bulletin Board online from 10 July to 11 November 2002, plus

dimensions variable

| |

It doesn't surprise me that "art critics" are now for the most part uncritical. Given the critical nature of much of contemporary art already, the notion of further criticism verges on redundancy. Although I must admit to liking critics that call out redundancies. Critical artists are far more valuable than critical critics. For example, a current online publication project that "talks back to Artforum via reenactment" was yesterday deemed unfit for access to this very forum—like it's ok for critics to continually work at usurping the control that artist's naturally have, yet it's not ok for artists to usurp the control that critics artificially have. Reenactments, like the memories that progenerate them, are a most critical form of redundancy. cf: 1072s. Kubrick suggests that curators are "never criticized for what they do," yet this month's Artforum letter section is all about critic's criticizing curators and vice-versa. Do I sense a suggestion of the notion that we need critics to teach us which artists are critical and which artists only appear to be critical? What exactly is the difference between being critical and only appearing to be critical? Is it perhaps the same as being really critical versus being virtually critical? [Actually, I like the notion of just appearing to be critical, and I'd love to know how to perfect such a look, as in, "I am not being critical, I only appear to be so. It's an artform I've perfected. (wink wink)"] Come to my basement where you'll see lots of art that doesn't "do" anything (except collect dust). There is a fair amount of honesty (I believe) in what mmutt writes about the "behind the scenes" of curating, but what is it that critics, curators, and artists are (actually/supposedly) being blamed for? Ultimately, I want to make big money selling my artwork, yet I more want to do it via virtual means (as opposed to real means, which is the system in place now). Most of the reason I'm (virtually) reenacting Artforum November 2002 is to learn its 'system' largely via a deconstructive process. And there is also the investigation of just how much blurring of the real and the virtual is the real publishing realm willing and/or able to accept. So far, the most immediate lesson to really sink in is that the lion share of what Artforum puts into print/pages is art gallery advertising, and not only are there more art gallery ads than anything else, there are only a handful of ads that promote something other than art galleries. Like almost all newsstand magazines, Artforum is foremost a vehicle for advertising, while "art matters" come second. Of course, the statistics on the side of advertising gain even more when one considers how exhibit reviews are at least partially advertising (although I personally see reviews also more advertising than anything else). [Are museum exhibits actually one of the highest forms of advertising? They certainly rank very high when it comes to adding "aura" to provenance.] So just maybe Currin's paintings command very high prices because Schjeldahl favorably advertises them. By the time I'm finished reenacting Artforum November 2002 I want to have a clear understanding as to why it is supposedly only ok for magazines and critic reviews to advertise and not ok for artists to advertise and review themselves, however I don't anticipate a foregone conclusion. I didn't have to read more than the first few paragraphs of what Muschamp writes in today's New York Times before the notion of writing something myself took over. Muschamp's first paragraph reads: "Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio have defined a new building type for the contemporary city: the urban viewing platform. Invention of this caliber doesn't turn up every day. Diller and Scofidio could spend the rest of their careers reworking this one idea over and over again and not be judged harshly for repeating themselves. The basic concept is that good, and its potential applications are various. Many cities will want to try out variations on the theme. But Boston will receive the first authentic edition in 2004, when the city's Institute of Contemporary Art is expected to open its doors." The "urban viewing platform" is in NOT a new invention created by Diller and Scofidio. Every time I visit the Philadelphia Museum of Art I also visit a quite remarkable "urban viewing platform." Of course, Philadelphia's "urban viewing platform" has already been embedded into popular culture via a climatic scene in the movie Rocky, as in "flying high now!" There is, however, much more culture embedded within Philadelphia's "Faire Mount" in that it reenacts the Acropolis, which, incidentally, is much closer to the invention of the "urban viewing platform" than anything Diller and Scofidio ever did or do. So let's not confuse invention with what is really reenactment. I didn't bother to finish reading Muschamp's piece because (I feel) its contents are predictable, thus I will write a little more about Philadelphia's viewing platform, which will probably be akin to things that Muschamp says. The stairs that Sylvester Stallone ran up in the movie also many times act as enormous theatrical seating with the head of the Benjamin Franklin ("inventor" of electricity, as long as invention awards are being passed around) Parkway as the stage and the Philadelphia skyline as backdrop. Beyond that, there are always a variety of life vignettes occurring on the steps and up in the Museum forecourt. I particularly like seeing wedding pictures taken up on the "viewing platform"/forecourt; it reminds of a similar scene I once saw at the Campidoglio in Rome, which, incidentally, is another great "urban viewing platform" (and the view from the Campidoglio is the Campo Marzio! Wow, Quondam and the Campidoglio actually have something very much in common. Does that mean Quondam is also a reenactment of an "urban viewing platform" My goodness, will reenactment wonders never cease?). Ah reenactment! I'm so glad you're there, especially since so many so easily forget. [I guess there is one reenactment that I would rather see not continue, and that is the fool Muschamp continually makes of himself, but even more the fool he continually makes of architecture. I think it's time to stop Muschamp from his ongoing making a fool of architecture.] As an artist, I welcome the notion of owners of my art work(s) making money via my artwork. I give art as gifts and I sell art, and in either case I wish the art and its owner the best. All this has given me a great idea, that is, to make the IRS the heir of all my artworks when I dead.What I find inspiring about Rachel Harrison's art work (at least what is pictured in Artforum November 2002) is that I can now look at my entire house as a museum containing/exhibiting numerous paintings, sculptures, photographs and installations. [joke] What comes after house/palace? Museum. What comes after museum? Pre-shrine.The issue boils down to control and how much an artist wants to control their art beyond the making of it. McElroy is right about the overall flexibility of contracts, and it does bode the artist well to be cognizant of the (somewhat easy) legal capability of 'designing' control. My personal inclination is that I do not want to control my art beyond my making of it (especially since some of my 'best' work operates under the notion of 'apposing' someone else's work). It seems only fair to respect artists that want to exercise more control, however. Perhaps it might even be worthwhile for art history to from now on record contemporary art and the controls (if any) that it comes with. [future question] "Was she a control artist or was she a no-control artist?" I just happened to watch Cremaster 4 and (half of) Cremaster 5 yesterday and last night for the first time. (Yes, there are boot-leg copies of these works floating around.) Not really knowing what to expect in terms of the whole product (of each episode), I found myself mostly bored through unengagement and also wondering what all the fuss was/is about. For sure, a lot of work went into the production(s), but in no way was artistic video production enormously surpassed. I also happened to have a set of videos from the Free Library of The Avengers (TV show) 1967 episodes, and, compared to Cremaster 4 & 5, they are more original/obscure, slyly twisted, far more engaging, and even more artistic! I even found myself thinking that MTV Spanish videos (of the last year) are better surreal works of art. Granted the comparison with 2002 music videos is not entirely fair since Cremaster 4 & 5 precedes videos of 2002, but when you compare Cremaster 4 and Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, which were produced at the same time, Priscilla simply seems more worthwhile. Now, if Barney had somehow made the narrative flow of Cremaster(s) like the narrative flow of Fischli and Weiss' Der Lauf Der Dinge, then he would have created a very superior work of art. I agree that Barney is not necessarily going for a "narrative flow," but since Cremaster 4 has an under-riding journey motif, as does Cremaster 5 somewhat, I think a consequential narrative along with all the theatricality would have manifest a higher grade product. As it stands, I have no idea what Barney was going for because it all seemed pointless outside of the notion of "art for art's sake." Even on just visual terms the work falters due to over redundancy. Saying that Barney does not consider himself a "movie-maker" (if that is indeed how Barney feels) carries the air of disingenuousness. Such posturing also creates a buffer against being criticized as a bad movie-maker. A movie that I think is akin to the doldrums of 4 & 5 is Visconti's Ludwig—as much as I was interested in the subject matter there, I still had to force myself to watch the whole thing. Since I so far only watched half of Cremaster 5, and have no intention of watch the rest anytime soon, I doubt I'll pursue seeing the rest of the series. I've probably already lost out just by viewing 4 & 5 on my TV while laying on the couch, rather than seeing the work on a large screen with an audience. [It just occurred to me that seeing anything in the privacy of one's home very much lessens the "obligation" of sitting though an entire performance, while also lessening the occasion to "zone out" because one can either just get up and do something else or just change the channel.] The series played at the Philadelphia Museum of Art a while back, but I found out about it after the fact—I would have gone to the "viewing" if I had known about it. Mind you, I would have been very tempted to yell out "Give me a break!" and "Oh my gosh, isn't this is the most amazing thing you've ever seen!" more than a few times. Seeing what I saw so far, however, and even under less that favorable circumstances, I'm still disappointed relative to all the hype. I'm glad I never went to any art school—I went to undergrad architecture school—because I'm now very appreicative of self-education, in that it is doable with better than satisfactory results. For example, it's recently become clear that I can more than hold my own when it comes to understanding Duchamp, as evidenced at the www Duchamp bulletin board. After many years of self-education one begins to realize that one is learning not only what is being taught, but also a lot of what is not being taught. The more I understand the value of self-education, however, the less value I see in academia, because academia very often chooses to ignore that which is not from academia. Imagine, for example, that some artist or art historian student or teacher at Yale recently discovered a heretofore unknown printing by Piranesi. Chances are this discovery would have been deemed worthy of fairly wide press coverage, and considered a significant contribution to the history of art. Of course, this never happened recently in academia, but some self-taught architect/artist did discovery a heretofore unknown printing of Piranesi's Ichnographia Campi Martii, published the finding online, and received confirmation via email from Piranesi scholar John Wilton-Ely (editor of the "complete" etchings of Piranesi) that indeed our knowledge of Piranesi's etching is not necessarily complete. Because this news did not come from academia, academia pays no attention to it, yet at the same time there is no question that academia's knowledge of Piranesi is now definitely lacking. I think any artist would agree that it would for sure be thrilling to personally discover something like a lost/unknown Michelangelo. In all honesty, I can now very much claim a visceral understanding of what that thrill might just really be like, and I also feel that I probably would have never learned this sensation if I went to art school. frond, et al: First off I am not an art historian. My only professional schooling (latter 1970s)/training is as an architect; I am registered but with a lapsed license. If anything, I am an independent, project oriented artist, and I engage a variety of media. Since the bulk of my effort over the last six years has been toward maintaining two net domains as the outlet for my endeavors, then perhaps yes I now am a 'practicing' net artist. (I really like the self publishing ability that comes with HTLM, and I've been working with that 'language' as a continual subtext to all the other work.) My prior commentary was admittedly extreme, but I wanted to make the point that academia sets an artificial range of parameters, and (one could say) that one theme that runs through some of my work is the ongoing investigation of accepted parameters, especially those most taken for granted, or those most seen as somehow being above reproach. A project that ultimately redefines parameters is, of course, very satisfactory, but not necessarily a fulfillment of an overriding goal from the start. All higher education is now a high priced consumer item, and I feel it should be recognized as such from the get go. Thus, for me at least, I find it to be a lot more artful/artistic when I can attain something extremely valuable, yet at the same spend relatively no money getting it. Suffice it to say that I was/am attempting to clearly describe, and indeed often manifest, a fundamentally alternative mode of operation via my 'work'. This does not automatically mean that I am then also trying to be better (than 'everyone else'), but if I do come across what appears to be a(n unwittingly accepted) mistake, I will see if I can "fix it." frond: Yes HTML is full parameters, and yes a sensitivity to parameters enhances ones skill/dexterity with HTML. You seem to mistakenly associate 'sensitivity' with aversion only. A sensitivity to parameters does not necessarily mean a likewise aversions to parameters. Parameters, as you suggest, are everywhere, and not exclusive to academia, thus your assertion that since I am not a Ph.D. means that I am just a "history buff" is just another (artificial) parameter. Using your parameters, therefore, I am a history buff that made a significant discovery pertaining to Piranesi that two centuries of art historian Ph.D.s did not. One could then say that either I significantly enhanced the status/effectiveness of history buff, or that I significantly reduced the status/effectiveness of Ph.D.s (specializing in Piranesi specifically). You can indeed pick which parameter you prefer. I hope you realize that your calling me a history buff (only) is a completely unresearched labeling, hence an incorrect setting of a parameter based on presumptions that, in this case especially, appears to be exactly the type of artificial parameters set up by academia. You've done nothing less than prove the very point that I was/am making. Remember, all reality is relative to the vastness of its container. I'll tell you how it's possible. For a good portion of the last ten years I redrew Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius via computer-aided design software— see www.quondam.com/53/5310.htm. I was essentially reenacting Piranesi in the hope of learning his process/intention. I used a large poster reproduction of the plan as reference. As a result, I have written and published online many articles regarding my findings. I also presented a paper in Belgium in 1999, but the paper has been deemed (by the academics running the conference) as not appropriate, i.e., it went against all prior accepted notions of what the Ichnographia Campus Martius represents. The paper, however, was already published by myself online. (It's not online now, but is within the forthcoming Somewhat Incompletely Piranesi.) After years of just looking at a reproduction of Piranesi's large plan, I finally (in 1999) went to the Fine Arts Library of the University of Pennsylvania to see an actual 1761 print version of the plan, and that is when I discovered that the reproduction (like all the other reproductions one finds in print) is indeed different in key areas of the plan than what one finds within the 'original' print at UPenn. I documented the differences with my digital camera and published them online as well. (It's not online now, but if you are good at web research, i.e. google search lauf campo marzio, you will find traces of what I have published.) Through my own experience, I have found it to be far more productive doing actual work than to spend time (and money) applying for grants. In no way do grants have anything to do with my own performance, nor do I see it reasonable to think that I can only perform if I have grants to do so. Furthermore, it is time for academia to realize/admit that publishing is no longer solely their domain. What work I do, I do as art projects, and art controlled by academia isn't the type of art that I do. Academia may (choose to) ignore my work, but that doesn't mean I am then the only one that knows what academia is missing. Einstein + Einstein = zwei Stein / zwei Stein + zwei Stein = Neuschwanstein / Neuschwanstien + Neuschwanstein = Vierzehnheilegen Hey, I was just plagiarized above by KurdtKobain. Get your own text. Playing the Pre-Shrine Curator So far the works include: The Underground Metropolitan Collection comprising (at least) three salvaged architectural artifacts from Whitemarsh Hall (a.k.a. Stotesbury Mansion) where the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection was kept in safe keeping during WWII—one piece, the larger marble slab, supports the painting Anonymous Saint in Bikini While Jesus is Walking on Water. Telephone Not Included 01 a kind of very practical coffee table modern sculpture thing Damien Hirst I Ain't no butts in this ashtray, etc. Critics Abuzz 1 Critics Abuzz 2 Critics Abuzz 3 Critics Abuzz 4 a group of small, inexpensively framed Ab/Ex paintings Infringement Complex (on the list tentatively) collection of over 100 small ur-hybrid thinking collages fulfilling their title Heilige Helena web search equinoctial augury to see what also comes with the picture Playing the Pre-Shrine Curator, the inaugural exhibit at Obscuranti of Olney, an individual as Gesamtkunstwerk production presently in progress. Viewer interactivity encouraged via reenactment of Gertrude Stein, hence "buy it while it's cheap." The is also the notion [within the theory of chronosomatics] that the operations of the mind, i.e. imagination, reenact the (physiological) operations of the body. For example, there is a fertile imagination, an assimilating imagination, a metabolic (creative/destructive) imagination, an electro-magnetic imagination, etc. According to the chronosomatic gauge, humanity in our time operates mostly via a combination of an assimilating and metabolic imagination. Perhaps the real rule of art is to in fact reference your sources. Hiding your sources only seeks to perpetuate the notion of undiluted artistic originality, which is all a myth to begin with, and a myth, moreover, that the art establishment (galleries, critics, universities, et al) charges dearly for inoculation thereof. thingsthatgo: go to the design-l archive at lists1.cac.psu.edu/archives/design-l.html and do a search of 'chronosomatics' and also a search of 'timepiece humanity'—this will lead to many letters on the subject written online since mid-1998. there are chronosomatic letters also in the architecthetics archive at www.jiscmail.ac.uk/lists/architecthetics.html where the same search will work. maxherman: I kind of already did my WTC site thing via the Ezeri Mester Memorial—ezeri mester is Hungarian for millennial master—but I am still interested in your Millennium Hut idea. Encouragement is probably the best I can offer now, however. [The following are excerpts from "Grandeurs and Miseries of Whitemarsh Hall" by Fiske Kimball, a text that is presented in full within chapter 16, "The Stotesburys," of Triumph on Fairmount by George and Mary Roberts.] "Adventures of the Great Isfahan" Down the long salon stretched a superb Isfahan carpet, on which too often cocktails were spilled. Mrs. Stotesbury had sent to the Museum for the great Isfahan rug, which came back next day much in need of cleaning. His will singled out the English portraits, the tapestries, two sets of furniture, the great Isfahan rug and the porcelains from Duveen to be sold. The result of the Metropolitan's taking Whitemarsh Hall was indirectly to enrich the Philadelphia Museum. The Stotesbury tapestries, the fine furniture and the great Isfahan, which had remained at the house, were sent at once to the Museum as loans. In November [1944] the remaining objects which Mr. Stotesbury's will had directed should be sold were removed from the Museum for an auction in New York. It was a butchery. One Romney, the Vernon Children brought $22,000, but no other painting fetched more than $10,000. The magnificent fifty-three foot Isfahan brought only $5,000. It had cost Stotesbury $90,000. [This deconstructed text is a partial introduction to Monument Hystérique, the quondam Underground Metropolitan Collection, soon to be featured online at Museumpeace.] google web search "trophy 04" appositional pick the second result and follow through. I went to the local gas station/convenience store to buy a pack of cigarettes Tuesday night. Waiting in line at the counter I noticed a picture of a hi-rise building implosion on the front page of (Monday's) Philadelphia Inquirer. I looked closer, and sure enough, the Louis I. Kahn designed Mill Creek Housing towers were imploded Sunday morning 24 November 2002. This past August, when I was going around taking pictures of Kahn's local (to) Philadelphia works for Somewhat Incompletely Louis I. Kahn, was the first and only time I every visited Mill Creek Housing. I did take a number of pictures of the towers and the likewise abandoned adjacent low-rise housing as well. There's no question that I especially treasure these pictures now. Somewhat Incompletely Louis I. Kahn is now among the works comprising Playing The Pre-Shrine Curator, the inaugural exhibit (scheduled for late-winter/early-spring 2003) at Obscuranti of Olney. Stephen Lauf, Readymade in Japan with Laser Print on Transparency (2002.11.29: found object (metal and glass picture frame) and laser print on transparency film). 1073b Then follow through to see In Case You Didn't Get It, that is, in case you didn't get it. And then view all the Critics Abuzz. One could argue that the whole point of visual art(s) is to indeed be visible. [Fortunately, there is at least sculpture for blind people.] Our present "age" of mass/netted communications offer artists a multitude of new ways to be visible, i.e., execute their 'craft', be it via images or words or moving images and words, etc. Speaking personally, when it comes to my art and the making of it, I'm usually the only person worth it for me to believe in, thus believing in myself is indeed the only way I'm "gonna do" it. I know what I'm working for (as opposed to chasing). I'm working for the final goal of being history [and I already made that clear in my first exhibit, Process Taking Its Own Shape, back in 1983]. contemplative joke: when filing my taxes, "I work at becoming famous" is how I fill in my occupation. No [island] doubt a full time job, but "nice work if you can get it." [Gosh, I think I just did my visible artwork for today. Boy, now I have another day off.] I SEE exactly what you mean! Did you hear me immaterially laughing? My invisible smile is probably my best work, but I'm so good at it that no one/no power ever sees it. I'm glad to see such quick observance. When welshsonnyo says, "don't listen to them invisibles" he actually admits to seeing and hearing the "invisibles" himself, thus ironically proving that the "invisibles" are not invisible at all. Let's not confuse putting on blinders with there actually being an invisibility.

Stephen Lauf

The Talking Back at Artforum Self Portrait

2002.12.02

digital text: all the Lauf text posted at the TALKBACK at Artforum online from 9 November to at least 2 December 2002

dimensions variable

|

illustrate some 31"x19.5" reenactments of The Large Glass I did in 1993. There were originally (I think) 12 in all. These three are all I have left. The rest are in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston private collections. If there really is an audience for this kind of Duchamp stuff, I might just make all of Museumpeace a Duchamp reenactment (of one kind or another), at least for some period of time. Is G. Farriz showing us that it is now a paradox to try and try again even if one does first succeed? Go in Museumpeace, and may Museumpeace be with you. So I was correct? You are indeed trying and trying again even though you already first succeeded? My mother speaks with a genuine German accented English, and so do I (when I want to amuse) for that matter. Gosh, I hope that stuff you write isn't supposed to be a French accented English, because that is completely lost in my translation. I just got done watching this great TV show called Rollover-Play. It's mostly a display of un-air-conditioned thespians followed by a reward ceremony lauding the best over-actor. I could barely hold back the tears. The above is an excerpt from: Stephen Lauf, Learning From Lacunae: A Progressive Inquiry of the Acquisition of Knowledge Via Reflection On What Is Not There (Philadelphia: Museumpeace, 2003), p. 19120. ad carceres a calce revocari I looked at Yvonne and Magdeleine Torn in Tatters at the Philadelphia Museum of Art this afternoon, and took some digital snapshots of the painting as well. Later, at home, looking at a close-up image of the painting's signature, I notice it is signed "Duchamp Sept 11". I find out the date means September 1911, but I still think the coincidence is interesting. Perhaps I'll start referring to the quondam World Trade Center towers as Yvonne and Magdeleine. There is a special Richard Hamilton Museum Study exhibit within the PMA Duchamp gallery--see www.philamuseum.org for details. I might upload some images of the exhibit at Museumpeace next month. Someone has left additional graffiti on Étant Donnés' back door--"BOAC Scoota Allegheny 2002". This graffiti was not there about a month ago. I have over 40 digital images of The Large Glass (in full and in detail) in situ at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The images were taken at various times since February 1999. Since all the contemporary art galleries of the PMA were renovated winter/spring 2000, I also have Large Glass in two different immediate "contexts". There is even one fortuitous shot of two real "bachelors" standing behind and seen through the glass. These images were taken for my own [artistic] use, but I have no problem with sharing some of them as long as I know what they will be further used for and that proper photographic credit for the image(s) is thereafter provided. Stephen Lauf www.quondam.com www.museumpeace.com Museum Trip 2001.03.25 entitles a display beginning at wmpc/01/0050.htm comprising a series of images recorded at the Philadelphia Museum of Art on 25 March 2001. These images, rendered here at approximately the size of slide images on a light table, are ordered in the exact sequence that they were taken. More than half of the images depict an investigation of what other works of art at the Philadelphia Museum are axial with The Large Glass. For example, immediately adjacent the Duchamp gallery are galleries containing the works of Brancusi and Twombly respectively. Directly above the Duchamp gallery is a room by 18th century Scottish architect Robert Adam. In the museum's other wing across the courtyard is a fine collection of American glass, (a fitting symmetrical counterpoint to The Large Glass), a collection of Pennsylvania German artifacts, and on the floor above a selection of temples from the Orient. Inspiration for this investigation derives from the very strong axial relationship between Duchamp's The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even and Jennewein's Western Civilization as clearly manifest on the Philadelphia Museum of Art's northern courtyard facade, as well as the quondam axial relationship between The Large Glass and Martin's Yara. Museum Trip 2001.03.25 further considers the other axial, albeit by chance, occurrences at Philadelphia with regard to The Large Glass, and, as chance would have it, it was during the recording of the Brancusi gallery that the chance 'discovery' of Étant Donnés inscripted back door occurred. The following was first sent today to the Design-L listserve: [The following is the first two paragraphs, etc. of "What the Hand Knows" by Calvin Tomkins. This articled first appeared in The New Yorker 2 May 1983. This article very much spurred my attitude toward CAD (computer aided design) and its relationship to draftsmanship and manual dexterity in general. It also very much stimulated the initiation of my 'career' as an artist. For the record, I received CAD training February 1983, and CAD equipment was delivered to Cooper and Pratt Architects (my employers then) April 1983.] "What the Hand Knows" One of our era's significant feats has been the separation of art from skill. In most English dictionaries, the two words are closely linked. "Art" spreads a wider net, of course; it is so variable in meaning that, according to Webster, it can be used as a synonym for "skill," "cunning," "artifice," and "craft"--"which, on the other hand, are not always synonymous among themselves." When it comes to the creation of works of art, most people would agree that something more than skill, cunning, artifice, and craft is required. Only in this century, however, has it been found possible and desirable to produce works of art whose making requires little skill or none whatsoever. Marcel Duchamp is generally thought to be the hero (or the villain, if you prefer) of this remarkable achievement. Duchamp's famous "ready-mades"--common manufactured objects, such as an iron bottle-drying rack and a snow shovel, selected and signed by the artist--undermined the whole tradition of the artist as a skillful maker while poking fun at the belief that artists were superior beings whose mere signature conferred value. Duchamp's ambition, as he explained it, was "to put painting once again at the service of the mind." European painting since Courbet had been primarily "retinal," he said--a matter of manual skill in applying paint to canvas. By choosing a factory made object of no aesthetic interest, which he might alter slightly or else leave untouched, Duchamp was calling attention, in his ironic way, to the fact that a work of art was also an intellectual act--a choice, a sum of decisions. (Years later, when an art historian taxed him with the fact that several of his ready-mades had in the course of time become highly prized works of sculpture--icons reproduced in all the art-history books--Duchamp smiled and said, "Nobody's perfect, hm?" [Five paragraphs later:] Anyone who goes around to the galleries these days, however, is bound to see a great deal of deliberately unskillful, clumsy-looking work. Jean Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and the other "graffiti artists" who have shifted their efforts from subways to shows in New York galleries and international "trend" exhibitions are much talked about this season, and the European and American neo-expressionists are still the hot ticket in SoHo. This slapdash, loosely figurative painting is usually viewed as a triumphant reaction to the austerities of Minimalism and Conceptualism. Perhaps it is; perhaps that is all it is. David Hockney, the English artist, has been saying recently that representational art was bound to make a comeback sooner or later; the reason its return took the form it has taken in neo-expressionist, "new image," and graffiti art, he said, is that these artists were never trained to draw. Some of our young geniuses gain an appearance of free hand drawing by projecting photographic images on their canvases and tracing them; the photograph is, among other things, an invaluable substitute for skill. [note: almost 20 years later Hockney makes well researched claims that even some older masters used projections to draw!] [When the CAD computer equipment finally arrived and was up and running at Cooper and Pratt Architects, we had one of those not-too-serious office competitions for naming the computer. I suggest we call it 'Duchamp' while Bernie (my CAD partner then) suggested 'Godot' (as in "Waiting for Godot"). As it happened, both Bernie's and my suggestion turned out to be fitting. What I personally experienced when CAD became my daily occupation was the sudden obsolescence of my (quite talented) drafting skills. I still used my hands to "draw," but my dexterity now amounted to making sure I pushed the right buttons--my mother very presciently at the time made the analogy to playing the piano. I started seeing the final drawings produced by either pen-plotter or electrostatic printer as sort of "ready-mades" or at least abundantly reproducible "originals" that I could merely add a signature to in order to confer them as "my" drawings. Luckily (and thanks to the words of Calvin Tomkins, I guess), I found an outlet for my quondam drafting skills in producing "art." I decided, however, that I no longer needed to exhibit skill because I had (access to) a machine that did that, thus I produced art that was (and sometimes still is) deliberately unskillful, intending to prove through such imperfect manifestations themselves that a hand indeed created the work. If nothing else, all of the above explains why a few years ago here at design-l I wrote that "perhaps it is more the case that the way we think influences the way we use tools."] Museum Trip 2002.09.15 is the latest edition of the MUSEUM TRIP series at