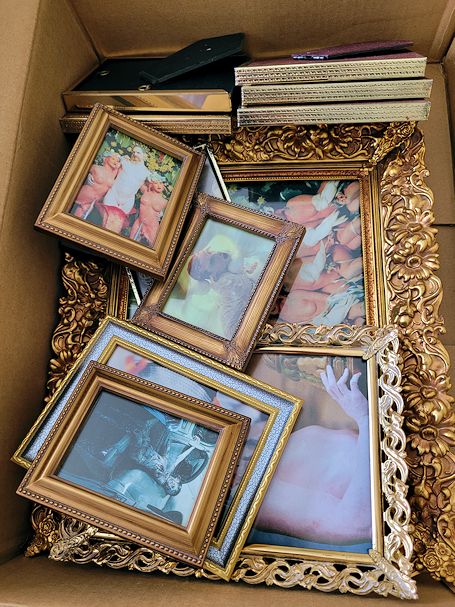

Unpacking Lauf's Forbidden Cremaster Collection

The first chapter is now over and a new chapter is soon to begin (thanks to ephemera galore).

2024.05.20

20240520_192116.jpg

The fun has already begun. The title of this new chapter is Collage Restraint.

2024.05.20

From The Discovery of Piranesi's Final Project:

20 May 2023 Saturday

Reading about precious artifacts being returned, albeit conditionally, to the Russian Orthodox Church reminded me of Constantine's use of Christianity to further secure his military efforts to re-unite the empire under himself. First, rather than persecute Christians, he welcomed them into his army, and second, on 27 October/28 October 312 before going into battle against Maxentius outside Rome, Constantine tells his soldiers to paint the sign of Christ on their shields because that's what the Christian god told him to do in a dream just before he woke up. Luckily for Constantine, the hoax worked.

2023.05.20

zero four one

2017.05.20

The Official Paradigm Shift thread

Seven Typical Plans of Ambiguity or Plan Atypical

The first typical plan of ambiguity arises when a detail is effective in several ways at once.

In the second typical plan of ambiguity two or more alternative meanings are fully resolved into one.

The condition for the third typical plan of ambiguity is that two apparently unconnected meanings are given simultaneously.

In the fourth typical plan of ambiguity the alternative meanings combine to make clear a complicated mind in the architect.

The fifth typical plan of ambiguity is a fortunate confusion...

In the sixth typical plan of ambiguity what is designed is contradictory or irrelevant and the user is forced to invent interpretations.

The seventh typical plan of ambiguity is that full of contradiction, marking a division in the architect's mind.

5, 6 and 7 are my favorites.

2008.05.20

hotrod architecture

Along with performance, the notion of 'extreme', taking something to an extreme, seems to be necessary to the concept of hotrodding as well.

[The] example of the 'sleeper' is especially provocative architecturally in that two extremes are present in the 'design'--the super engine inside and the "rusting, paint peeling off everywhere a thin crack line runs across the windshield etc. etc." facade.

Suddenly I want to design architecture along the lines of looking like a dilapidated shack on the outside yet like the Hall of Mirrors a la Versailles on the inside.

Wait a minute. Ludwig II as hotrod sleeper architecture client! Who knew?

2005.05.20

hotrod architecture

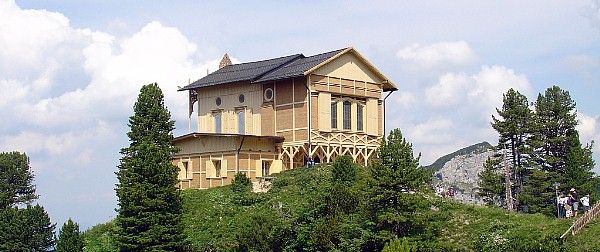

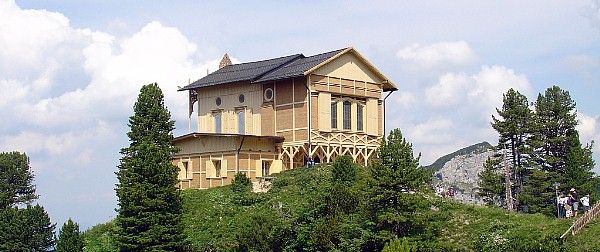

In the case of Schachen, the building was to perform as a retreat, a "mountain refuge." The "Swiss chalet" motif certainly upholds the notion of a place of retreat in the Bavarian Alps. Yet inside there is an overly opulent "Turkish Hall" which offers retreat in a very extreme way, you could say both physically and metaphysically, a retreat virtually into dreamland, like a psychedelic trip even. (And who knows what "drugs" might have been done there.)

Architecture performs on all kinds of levels, from the structural (the most necessary and literal performance), to the mechanical (and here plumbing and electricity seem the most pervasive), to the programmatic, to even the symbolic. Doors have to perform, windows have to perform, toilets have to perform, roofs have to perform, etc., etc..

Perhaps it's as simple as taking any performance aspect of architecture to an extreme and you then have a design methodology analogous to hot rodding.

2005.05.20

hotrod architecture

Picking up on "stealth communication with other experts," I'm recalling a detail from Kahn's Esherick House. I think in the hall right as you enter the house there is a light switch panel unlike anything I've ever seen before. Not only are there like eight toggle switches in a row, but the panel is set on the wall vertically, as opposed to the traditional horizontal mounting. Granted this is just a small detail, but, given that the building dates from 1959-61, such a light switch panel seems extreme (and I certainly thought that when I first saw it in 1977), but also elegantly simple in its execution.

While I'm "in" the Esherick House, the windows here also have an extreme-ness to them, and these windows are very much integral to the architecture.

And now I'm thinking of the enormous light hoods that "light" the communal spaces of Kahn's Erdman Hall dormitory at Bryn Mawr. Again there is this extreme-ness in terms of how light enters the space, and the resultant effect is very much part of what makes Kahn's architecture "great".

And now thinking further about "windows," my favorite panes of glass remain those at either end of the quondam Liberty Bell Pavilion (vintage 1976). While not a makeover, per se, the detailing of this building has an extreme-ness to it overall, even to the point where the roof/ceiling is split right down the middle so as to not disrupt the axis of Independence Hall. And even aesthetically, if you look at this building closely, it wouldn't be a stretch to say it has a 'hot rod' feel to it. And, as to performance, as much as most didn't like the building, representatives of the National Park Service will nonetheless admit that it served its purpose of allowing thousands and thousands of visitors to see, stand by, and touch the Liberty Bell very well.

Anyway, I never expected to be thinking about Kahn and Mitchell/Giurgola architecture in conjunction with "hot rodding", so again, "Who knew?"

2005.05.20

|